I'm incredibly optimistic about the state of web development in 2025. It feels like you can build anything, and it's never been this easy or this cheap. AI is the thing everyone talks about, and it's been a great unlock — letting you build things you didn't know how to do before and simply build more than ever.

But I don't think that's the complete picture. We also have so many more tools and platforms that make everything easier. Great frameworks, build systems, platforms that run your code, infrastructure that just works. The things we build have changed too. Mobile phones, new types of applications, billions of people online. Gmail, YouTube, Notion, Airtable, Netflix, Linear — applications that simply weren't possible before.

This is a retrospective of being a web developer from when I was growing up in the 1990s until today. Roughly 30 years of change, seen through the lens of someone who lived it — from tinkering with HTML in a garage in a small Swedish town to working as an engineer at a YC startup in Barcelona.

The Static Web

"View Source was how you learned"

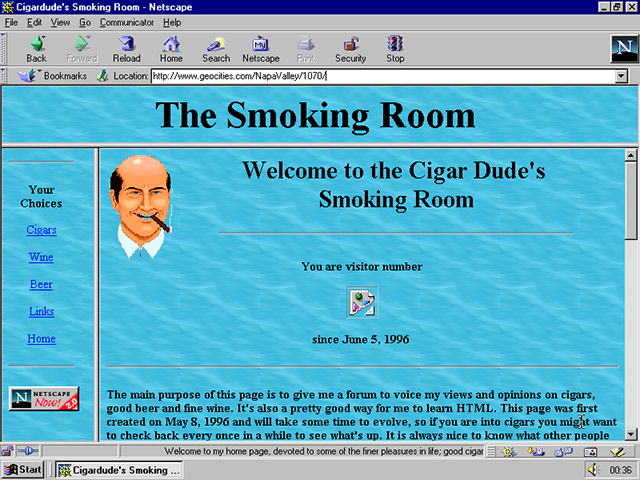

Let's go back to when the web felt like a frontier. The late 90s were a magical time — the internet existed, but nobody really knew what it was going to become. And honestly? That was part of the charm.

My first website lived on a Unix server my dad set up at his office. He gave me a folder on artmann.se, and suddenly I had a place on the internet. My own little corner of this new world. All I needed was Notepad, some HTML, and an FTP client to upload my files. It was a creative outlet — I could write and publish anything I was interested in that week, whether that was cooking, dinosaurs, or a funny song I'd heard. No gatekeepers, no approval process. Just me and a text editor.

This was the era of learning by doing — and by reading. There were no YouTube tutorials or Stack Overflow. When you wanted to figure out how someone made their site look cool, you right-clicked and hit "View Source." For anything deeper, you needed books. Actual physical books. I later borrowed a copy of Core Java, and that's how I learned to actually code. You'd sit there with an 800-page tome next to your keyboard, flipping between chapters and your text editor. It was slow, but it stuck.

When it came to HTML, you'd see a mess of <table> tags, <font color="blue">,

and spacer GIFs — those transparent 1x1 pixel images we used to push things

around the page. It was janky, but it worked.

CSS existed, technically, but most styling happened inline or through HTML

attributes. Want centered red text?

<font color="red"><center>Hello!</center></font>. Want a three-column layout?

Nested tables. Want some spacing? Spacer GIF. We were building with duct tape

and enthusiasm.

The real pain came when you wanted something dynamic. A guestbook, maybe, or a hit counter — the badges of honor for any self-respecting homepage. For that, you needed CGI scripts, which meant learning Perl or C. I tried learning C to write CGI scripts. It was too hard. Hundreds of lines just to grab a query parameter from a URL. The barrier to dynamic content was brutal.

And then there was the layout problem. Every page on your site needed the same

header, the same navigation, the same footer. But there was no way to share

these elements. No includes, no components. You either copied and pasted your

header into every single HTML file (and god help you if you needed to change

it), or you used <iframe> to embed shared elements. Neither option was great.

Browser compatibility was already a nightmare. Netscape Navigator and Internet Explorer rendered things differently, and you'd pick a side or try to support both with hacks. "Best viewed in Netscape Navigator at 800x600" wasn't a joke — it was a genuine warning.

But here's the thing: despite all of this, it was exciting. The web was the great equalizer. Before this, if you wanted to publish something, you needed access to printing presses or broadcast equipment. Now? Anyone with a text editor and some curiosity could reach the entire world. Geocities and Angelfire gave free hosting to millions of people who just wanted to make something. Web rings connected communities of fan sites. It was chaotic and beautiful.

There were no "web teams" at companies. If a business had a website at all, it was probably made by "the person who knows computers." The concept of a web developer as a profession was just starting to form.

The tools were primitive, the sites were ugly by today's standards, and

everything was held together with <br> tags and good intentions. But that

first era planted the seed: the web was a place where anyone could build and

share. That idea has driven everything since.

The LAMP Stack & Web 2.0

"Everything was PHP and MySQL"

The dot-com bubble burst in 2000, but the web kept growing. And for those of us who wanted to build things, this era changed everything. The barriers started falling, one by one.

The first big unlock for me was PHP. After struggling with C

for CGI scripts — hundreds of lines just to read a query parameter — PHP felt

like a revelation. I installed XAMPP, which

bundled Apache, MySQL, and PHP together, and suddenly I could build dynamic

websites. Need to grab a value from the URL? $_GET['name']. That's it. One

line. No memory allocation, no compiling, no cryptic error messages. Just write

your code, save the file, refresh the browser.

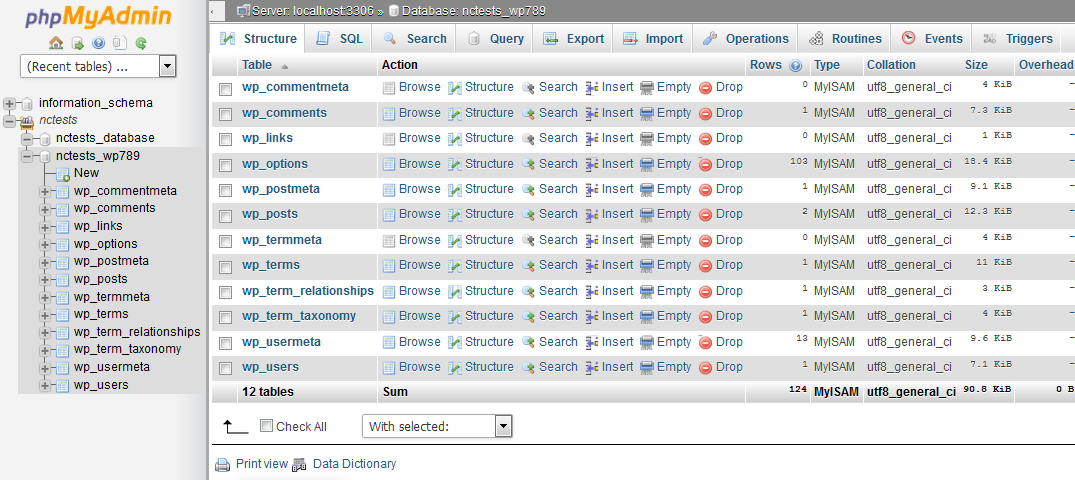

PHP also solved the layout problem that had plagued the static era.

<?php include 'header.php'; ?> at the top of every page, and you were done.

Change the header once, it updates everywhere. It sounds trivial now, but this

was genuinely exciting. The language had its warts — mixing HTML and logic in

the same file, inconsistent function naming, mysql_real_escape_string — but it

didn't matter. PHP was accessible. You could learn it in a weekend and build

something real. Shared hosting cost $5 a month and came with

cPanel and phpMyAdmin. The

barrier to getting online had never been lower.

With PHP came MySQL — they were a package deal, the "M" and "P" in LAMP. Every tutorial, every hosting provider, every CMS assumed you were using MySQL. It worked, mostly. But if you were doing anything with international text, you were in for pain. The default encoding was latin1, and UTF-8 support was a minefield. I lost count of how many times I saw "ä" instead of "ä" because something somewhere had the wrong character set. You'd fix it in the database, then discover the connection wasn't using UTF-8, then find out the HTML wasn't declaring the right charset. Encoding issues haunted this entire era.

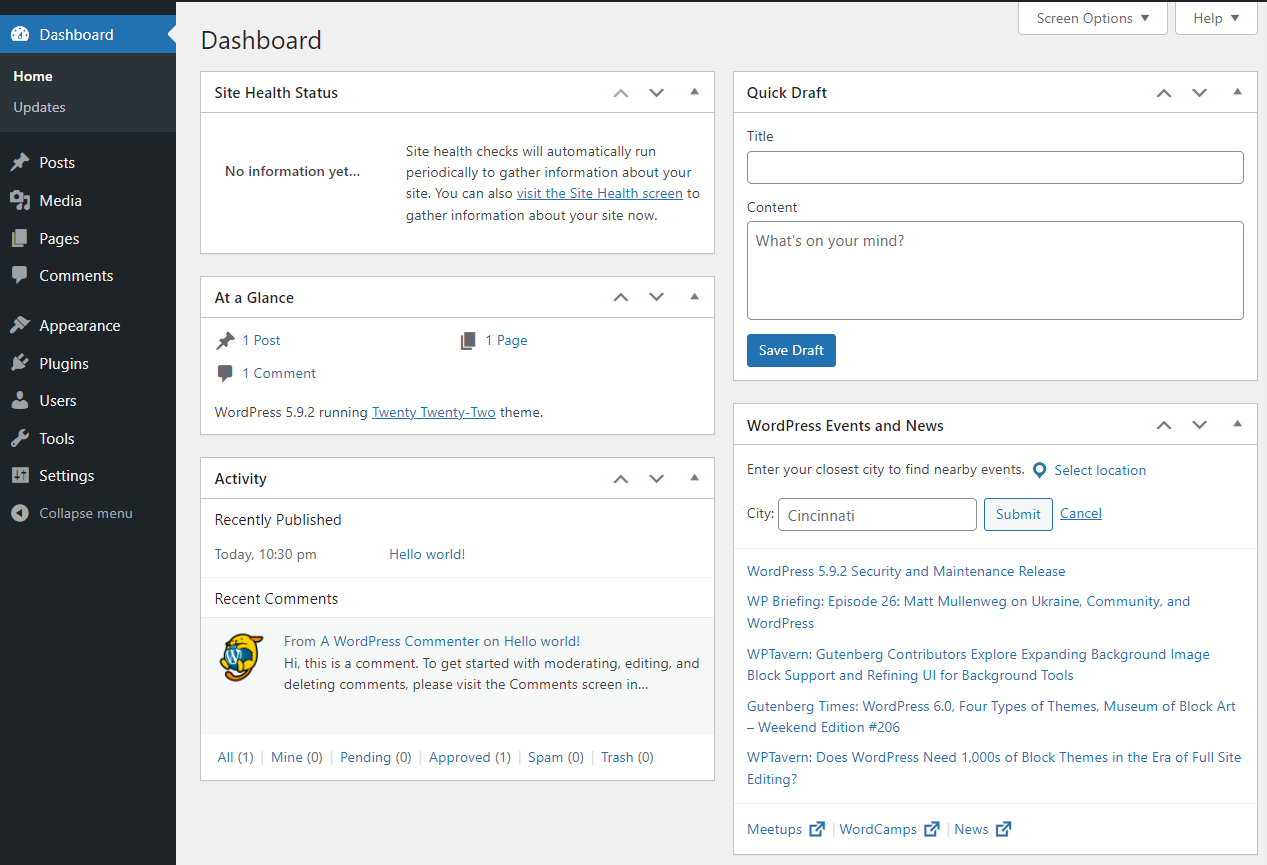

WordPress launched in 2003 and it's hard to overstate how much it changed the web. Before WordPress, if you wanted a website, you either learned to code or you paid someone who did. There wasn't really a middle ground. WordPress created that middle ground. You could install it in five minutes, pick a theme, and start publishing. No PHP knowledge required.

For non-technical people, this was transformative. Bloggers, small businesses, artists, restaurants — suddenly everyone could have a professional-looking website. The "blogger" emerged as a cultural phenomenon. People built audiences and careers on WordPress blogs. The platform grew so dominant that for many people, it simply was the web. I once talked to a potential customer who referred to the WordPress admin as "the thing you edit websites in." They didn't know it was a specific product — they thought that's just how websites worked.

For developers, WordPress became the default answer to almost every project. Need a blog? WordPress. Portfolio site? WordPress. Small business site? WordPress. E-commerce? WooCommerce on WordPress. It wasn't always the right tool, but it was always the easy answer. The ecosystem of themes and plugins meant you could assemble a fairly complex site without writing much code. This was both a blessing and a curse — WordPress sites were everywhere, but so was the technical debt of plugin soup and theme customizations gone wrong.

Then Google released Gmail in April 2004, and it broke everyone's brains a little.

To understand why Gmail mattered, you have to remember what email was like before it. Hotmail and Yahoo Mail gave you something like 2-4 megabytes of storage. That's not a typo — megabytes. You had to constantly delete emails to make room for new ones. Attachments were a luxury. Storage was expensive, and free services were stingy with it.

Gmail launched with 1 gigabyte of free storage. It felt almost absurd — 500 times more than Hotmail. Google's message was clear: stop deleting, start searching. But storage wasn't even the most revolutionary part.

Gmail was a web application that felt like a desktop application. You could read

emails, compose replies, switch between conversations, and archive messages —

all without the page reloading. It was fast, fluid, and unlike anything else in

a browser. The technology behind it was

AJAX — Asynchronous

JavaScript and XML. The XMLHttpRequest object let you fetch data from the

server in the background and update parts of the page dynamically. The technique

wasn't new, but Gmail showed what was possible when you built an entire

application around it. Suddenly we weren't just making web pages — we were

making web apps.

Google Maps followed in 2005 and pushed this further. Before Google Maps, online maps were painful. You'd get a static image, and if you wanted to see what was to the left, you'd click an arrow and wait for a whole new page to load. Google Maps let you click and drag the map itself, loading new tiles seamlessly as you moved around. It felt like magic. This was the moment "Web 2.0" got its name — rounded corners, gradients, drop shadows, and pages that updated without reloading. The web wasn't just for documents anymore.

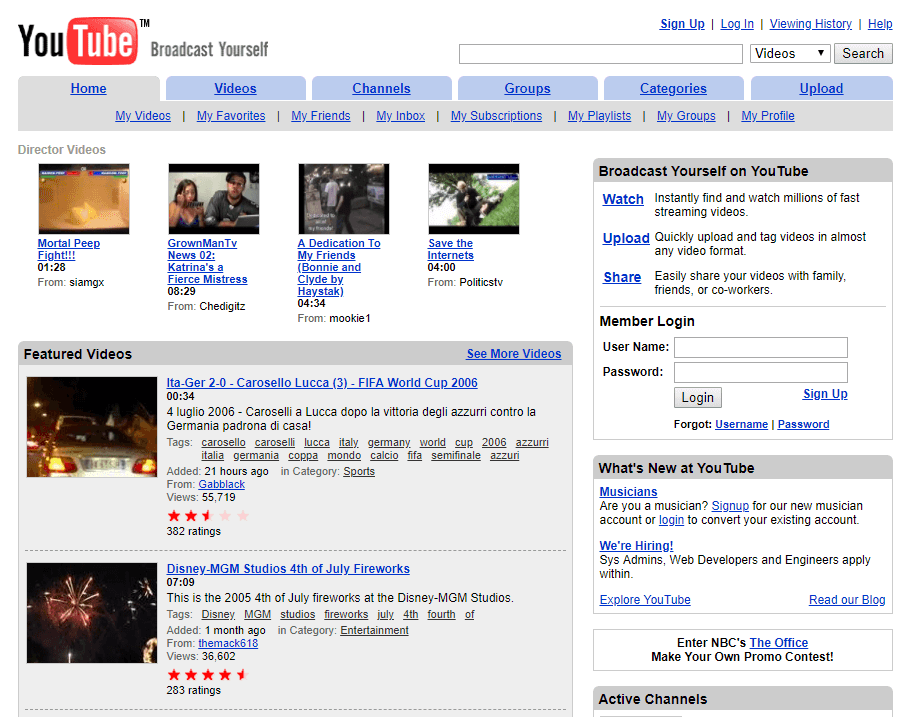

The mid-2000s brought a wave of platforms that would reshape everything. Video on the web had been a nightmare. You needed plugins — RealPlayer, QuickTime, Windows Media Player — and they were all terrible. You'd click a video link and wait for a chunky player to load, if your browser even had the right plugin installed. Half the time you'd just download the file and watch it locally. YouTube launched in 2005 and swept all of that away. Embed a video, click play, it works. Flash handled the playback (we'd deal with that problem later), but the user experience was seamless. Video went from a technical hassle to something anyone could share.

Twitter arrived in 2006 with its 140-character limit and deceptively simple premise. Facebook opened to the public the same year. Social networks moved from niche to mainstream almost overnight. These weren't just websites — they were platforms built on user-generated content. The web was becoming participatory in a way it hadn't been before. Everyone was a potential publisher.

JavaScript was still painful, though. Browser inconsistencies were maddening — code that worked in Firefox would break in Internet Explorer 6, and vice versa. You'd spend hours debugging something only to discover it was a browser quirk, not your code. Event handling worked differently across browsers. Basic DOM manipulation required different methods for different browsers. It was exhausting.

jQuery arrived in 2006 and papered over all of it.

$('#element').hide() worked everywhere. $.ajax() made AJAX calls simple.

Animations that would take dozens of lines of cross-browser code became

one-liners. The library was so dominant that for many developers, jQuery was

JavaScript. We didn't write vanilla JS — we wrote jQuery. Looking back, it was

also a crutch. We avoided learning how the browser actually worked because

jQuery handled it for us. But at the time? It was a lifesaver.

This era had its share of problems we just accepted as normal. Security was an

afterthought — SQL injection was everywhere because we were concatenating user

input directly into queries. We'd see code like

"SELECT * FROM users WHERE id = " + $_GET['id'] in tutorials and think nothing

of it. Cross-site scripting was rampant. We didn't really understand the risks

yet.

Version control, if you used it at all, was probably

Subversion. Commits felt heavy and permanent.

Branching was painful enough that most people avoided it. A lot of developers I

knew just had folders named project_backup_final_v2_REAL_FINAL. The idea of

committing work-in-progress code felt wrong — you committed when something was

done.

And then there was the eternal refrain: "works on my machine." There were no

containers, no standardized environments. Your local setup was probably XAMPP on

Windows, but the server was Linux with a different PHP version and different

extensions installed. Getting code running in production meant hoping the

environments matched, and they often didn't. You'd debug issues that only

existed on the server by adding echo statements and refreshing the page.

Package management didn't exist in any real sense. You wanted a JavaScript

library? Go to the website, download the zip, extract it, put it somewhere in

your project, and hope you remembered which version you had. Everything lived in

a /js folder, manually managed. PHP was similar — you'd copy library files

into your project and maybe forget to update them for years.

The way teams worked was different too. There were no product managers on most teams I knew about. No engineering managers. If you worked at a company with a website, you were probably "the web guy" or part of a tiny team — maybe a designer and a developer, maybe just you. Processes were informal. You'd write code, test it by clicking around, upload it via FTP, and hope for the best. Code review wasn't a thing — you just committed and moved on. If something broke in production, you'd SSH in and fix it live, hands sweating.

The term "best practices" existed, but they varied wildly. Everyone was figuring it out as they went.

Despite all of this — or maybe because of it — the energy was incredible. The web felt like it was becoming something bigger. AJAX meant we could build real applications. Social platforms meant anyone could have an audience. PHP and cheap hosting meant anyone could ship. The professionalization of web development was just beginning. Rails had launched in 2004 and was gaining traction with its "convention over configuration" philosophy, promising a more structured way to build. The stage was being set for the next era.

But for now, we were happy with our LAMP stacks, our jQuery plugins, and our dreams of building the next big thing.

The Framework Wars

"Rails changed everything, then everyone copied it"

The late 2000s brought a shift in how we thought about building for the web. The scrappy PHP scripts and hand-rolled solutions of the previous era started to feel inadequate. We were building bigger things now, and we needed more structure. The answer came in the form of frameworks — and one framework in particular set the tone for everything that followed.

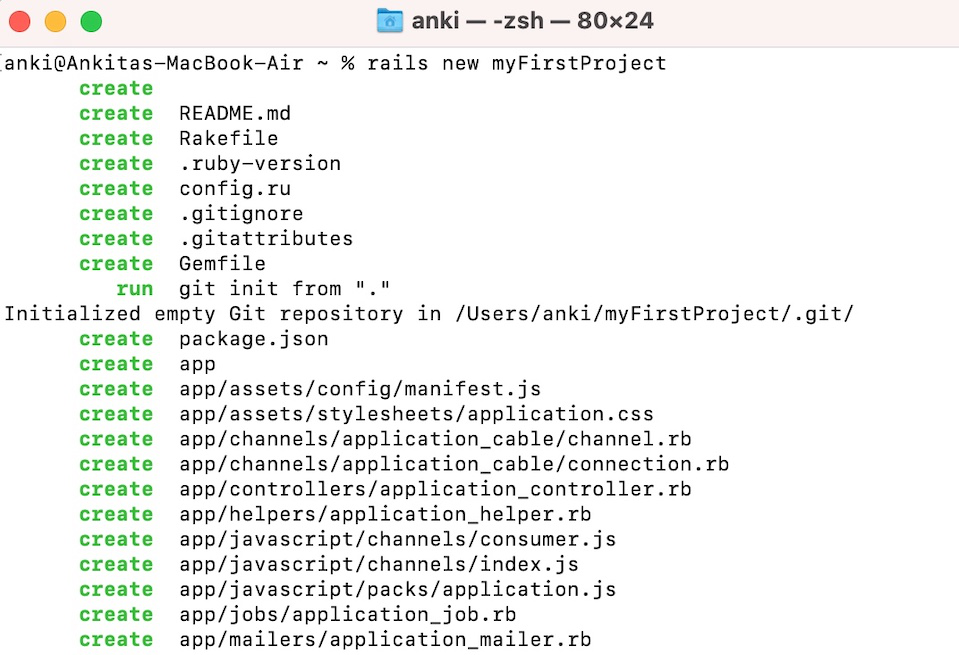

Ruby on Rails had launched in 2004, but it really hit its stride around 2007-2008. The philosophy was seductive: convention over configuration. Instead of making a hundred small decisions about where files should go and how things should be named, Rails made those decisions for you. Follow the conventions and everything just works. Database tables map to models. URLs map to controllers. It was opinionated in a way that felt liberating rather than constraining.

Rails also introduced ideas that would become standard everywhere: migrations for database changes, an ORM that let you forget about SQL most of the time, built-in testing, and a clear separation between models, views, and controllers. The MVC pattern wasn't new — it came from Smalltalk in the 1970s — but Rails brought it to web development in a way that stuck. Suddenly every framework, in every language, was copying Rails. Django did it for Python. Laravel did it for PHP. CakePHP and CodeIgniter had already been doing something similar, but Rails set the template that everyone followed.

The productivity gains were real. A single developer could build in a weekend what used to take a team weeks. Startups loved it. Twitter was built on Rails. GitHub was built on Rails. Shopify, Airbnb, Basecamp — all Rails. The framework became synonymous with startup speed.

But Rails only solved part of the problem. You still had to get your code onto a server somehow.

In the PHP era, deployment meant FTP. You'd connect to your shared host and upload files. It was simple but terrifying — one wrong move and you'd overwrite something important. For more serious setups, you might SSH into a server, pull the latest code from SVN, and restart Apache. At one company I worked at, we had a system where each deploy got its own folder, and we'd update a symlink to point to the active one. It worked, but it was all manual, all custom, and all fragile.

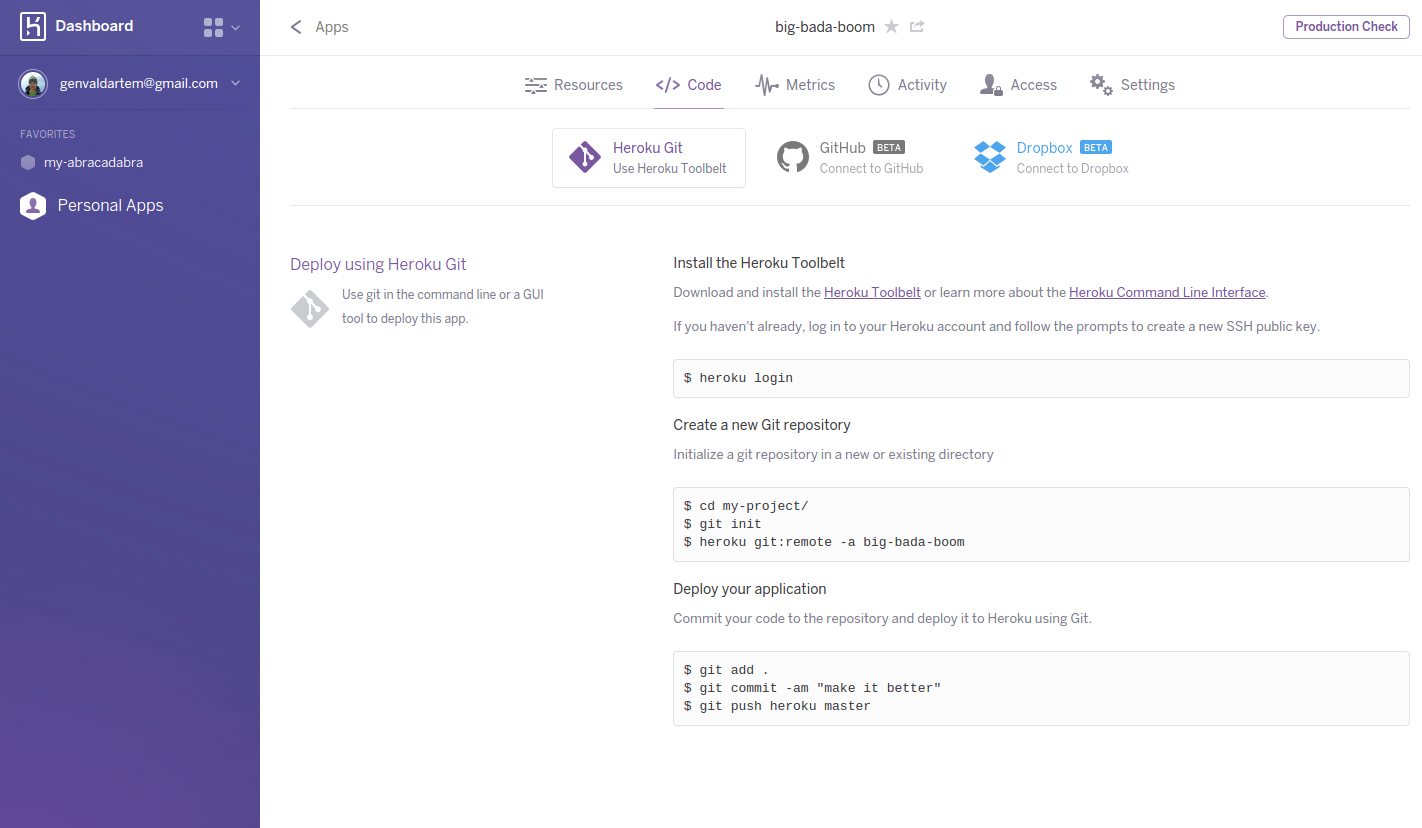

Heroku changed this completely. It launched in 2007 and

gained traction around 2009-2010, and the pitch was almost too simple to

believe: just push your code to a Git repository and Heroku handles the rest.

git push heroku main and your app was deployed. No servers to configure, no

Apache to restart, no deployment scripts to maintain. It scaled automatically.

It just worked.

This was a new concept — what we'd later call Platform as a Service. You didn't manage infrastructure; you just wrote code. Heroku also popularized ideas that would become foundational, like the Twelve-Factor App methodology: stateless processes, config in environment variables, logs as streams. These principles were designed for cloud deployment, and they shaped how a generation of developers thought about building applications.

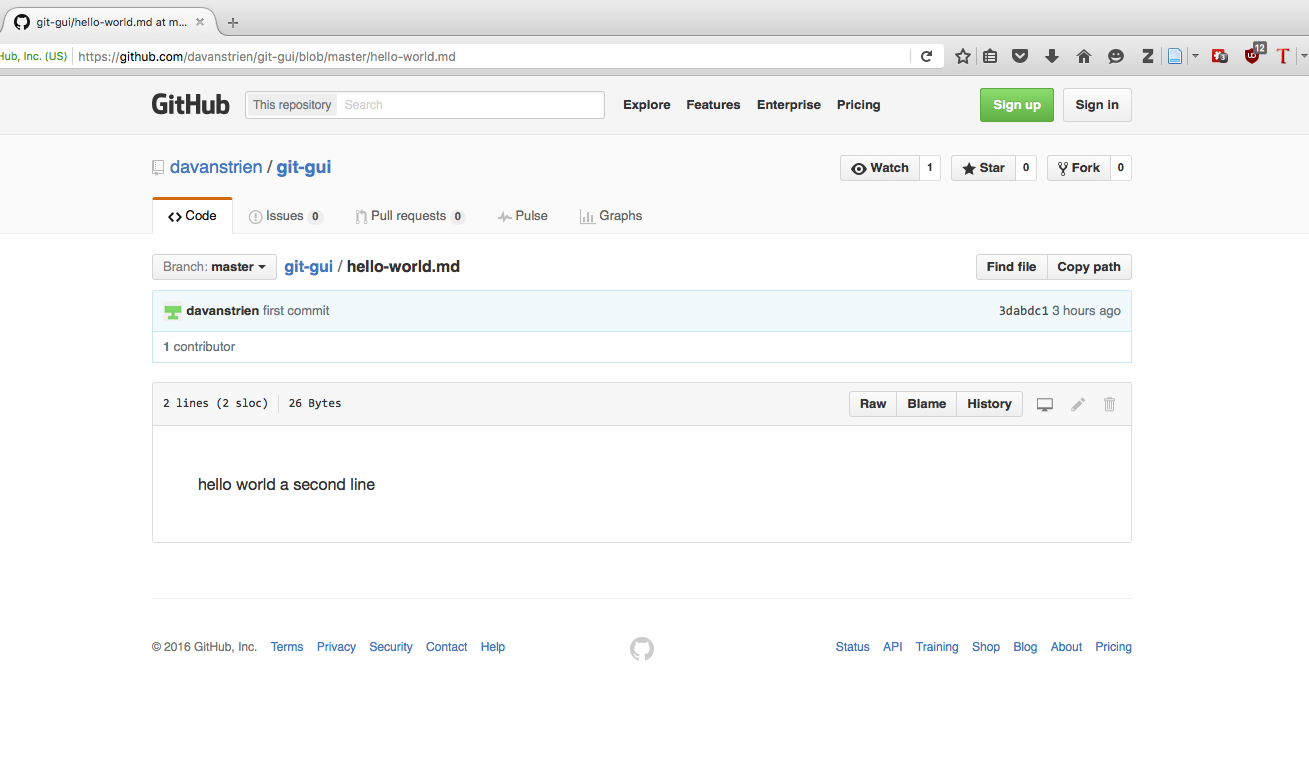

Speaking of Git — that was the other revolution happening simultaneously. GitHub launched in 2008, and it changed everything about how we collaborated on code.

Version control before Git was painful. Subversion was the standard, and it worked, but it was centralized and heavy. Every commit went straight to the server. Branching was technically possible but so cumbersome that most teams avoided it. You'd see workflows where everyone committed to trunk and just hoped for the best. Merging was scary. The whole thing felt fragile.

Git was different. It was distributed — you had the entire repository on your machine, and you could commit, branch, and merge locally without ever talking to a server. Branches were cheap. You could create a branch for a feature, experiment freely, and merge it back when you were done. Or throw it away. It didn't matter. This felt revolutionary after SVN's heaviness.

But Git alone was just a tool. GitHub made it social. Suddenly you could browse anyone's public code, see their commit history, fork their project and make changes. The pull request workflow emerged — you'd fork a repo, make changes on a branch, and submit a pull request for the maintainer to review. Open source exploded. Contributing to a project went from "email a patch to a mailing list" to "click a button and submit your changes." The barrier to participation dropped dramatically.

GitHub also quietly normalized code review. When you're submitting pull requests, someone has to look at them before merging. Teams started doing this internally too — not just for open source, but for all their code. This was a genuine shift in how software got built. Code that used to go straight from your editor to production now had a stop in between where someone else looked at it.

Around the same time, the ground was shifting under our feet in a way we didn't fully appreciate yet. In 2007, Apple released the iPhone. In 2008, they launched the App Store. And suddenly everyone was asking the same panicked question: do we need an app?

The mobile web was rough in those days. Websites weren't designed for small screens. You'd load a desktop site on your phone and pinch and zoom and scroll horizontally, trying to make sense of it. Some companies built separate mobile sites — m.example.com — with stripped-down functionality. But native apps felt like the future. They were fast, they worked offline, they could send push notifications. "There's an app for that" became a catchphrase.

This created a kind of identity crisis for web developers. Were we building for the web or for mobile? Did we need to learn Objective-C? Was the web going to become irrelevant?

The answer, eventually, was responsive design. Ethan Marcotte coined the term in 2010, describing an approach where a single website could adapt to different screen sizes using CSS media queries. Instead of building separate mobile and desktop sites, you'd build one site that rearranged itself based on the viewport. The idea took a while to catch on — it was more work upfront, and the tooling wasn't great yet — but it pointed the way forward.

Bootstrap arrived in 2011 and made responsive design accessible to everyone. Twitter's internal team had built it to standardize their own work, but they open-sourced it and it spread like wildfire. Suddenly you could drop Bootstrap into a project and get a responsive grid, decent typography, and styled form elements out of the box. Every website started looking vaguely the same — the "Bootstrap look" became its own aesthetic — but for developers who weren't designers, it was a godsend. You could build something that looked professional without learning much CSS.

For many of us, Bootstrap was our first component library, our first design system. It paved the way for everything that followed. Google released Material Design in 2014, bringing their opinionated design language to the masses.

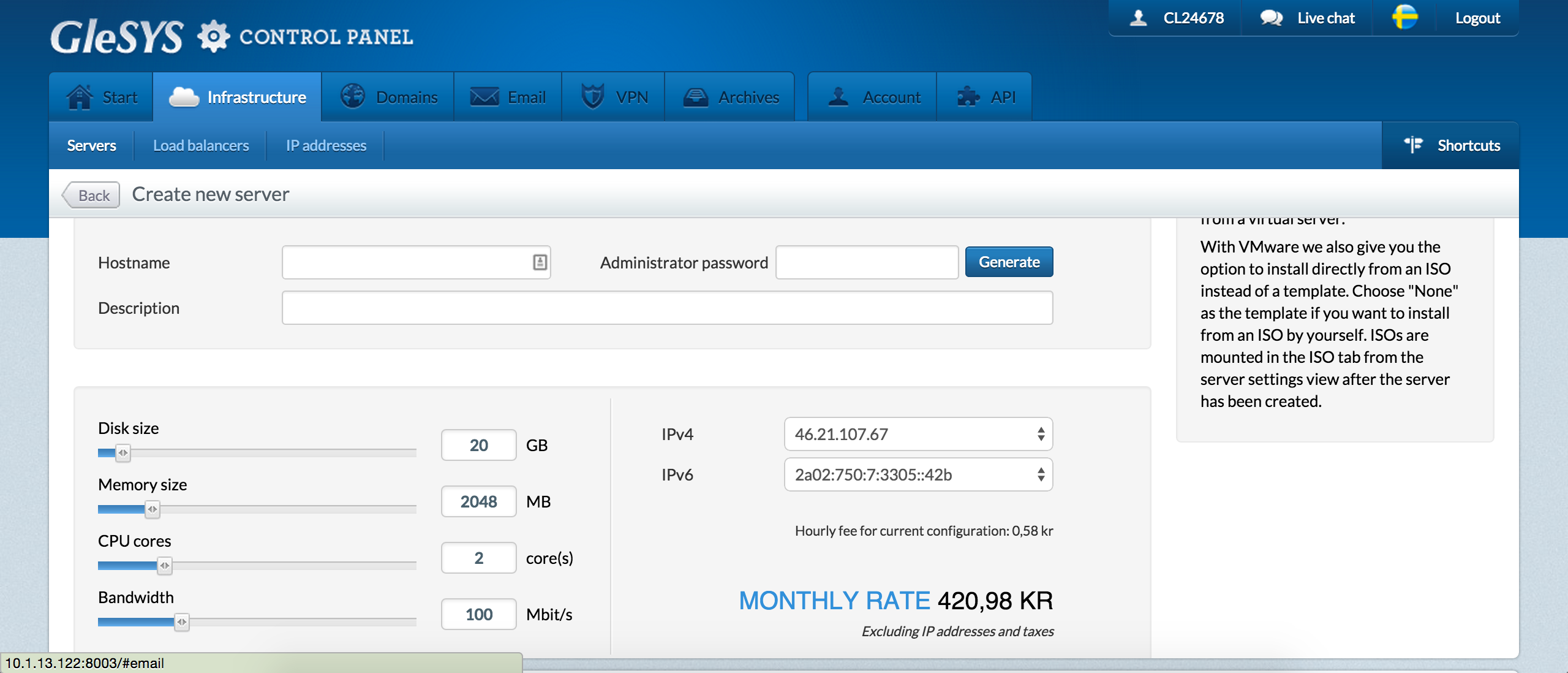

Meanwhile, the infrastructure beneath the web was transforming. I worked at Glesys during this period, a Swedish hosting company similar to DigitalOcean. We were part of this shift from physical servers to virtual ones. Before VPS providers, if you needed a server, you either rented a physical machine in a data center or you bought one and colocated it somewhere. You'd pick the specs upfront and you were stuck with them. Needed more RAM? That meant physically installing new hardware.

Virtual private servers changed this. You could spin up a server in minutes, resize it on demand, and throw it away when you were done. DigitalOcean launched in 2011 with its simple $5 droplets and friendly interface. AWS had been around since 2006, but it was complex and enterprise-focused. The new wave of VPS providers democratized server access — suddenly a solo developer could have the same infrastructure flexibility as a large company.

AWS did solve one problem elegantly: file storage. S3 gave you virtually unlimited storage that scaled automatically and cost almost nothing. Before S3, handling user uploads was genuinely hard. Where do you store them? What happens when you have multiple servers? How do you back them up? S3 made all of that someone else's problem. You'd upload files to a bucket and get a URL back. Done.

Node.js arrived in 2009 and scrambled everyone's assumptions. Ryan Dahl built it on Chrome's V8 JavaScript engine, and the pitch was simple: JavaScript on the server. For frontend developers who'd been writing JavaScript in the browser, this was intriguing. You could use the same language everywhere. For backend developers, the reaction was more skeptical — JavaScript? On the server? That toy language we use for form validation?

Node had some genuinely interesting ideas. Non-blocking I/O meant a single thread could handle thousands of concurrent connections without breaking a sweat. It was perfect for real-time applications — and every Node tutorial seemed to prove this by building a chat app. If you went to a meetup or read a blog post about Node in 2010, you were almost certainly going to see a chat app demo.

In practice, though, Node was still a curiosity during this era. Most production web applications were still Rails, Django, or PHP. The npm ecosystem was young and sparse. Node felt like the future, but the future hadn't quite arrived yet. Its real impact would come a few years later — and ironically, most developers' first meaningful interaction with Node wouldn't be building servers at all. It would be running build tools.

The NoSQL movement was also picking up steam. MongoDB launched in 2009 and became the poster child for a different way of thinking about data. Instead of tables with rigid schemas, you had collections of documents. Instead of SQL, you had JSON-like queries. The pitch was flexibility and scale — schema-less data that could evolve over time, and horizontal scaling built in from the start.

Not everyone needed this, of course. The joke was that startups would choose MongoDB because they might need to scale to millions of users, then spend years with a few thousand users and wish they had proper transactions. But MongoDB was easy to get started with, and it fit naturally with JavaScript and JSON. For certain use cases — rapid prototyping, document-oriented data, truly massive scale — it was genuinely good. The memes about MongoDB losing your data were unfair, mostly.

The startup ecosystem was in full swing by this point. "Software is eating the world," Marc Andreessen declared in 2011, and it felt true. Every industry was being disrupted by some startup. Lean Startup methodology had developers shipping MVPs and iterating based on data. The tools had gotten good enough that a small team really could compete with incumbents.

How we worked was changing too. Agile and Scrum had been around since the early 2000s, but they went mainstream during this era. Suddenly everyone was doing standups, sprint planning, and retrospectives. Some teams embraced it thoughtfully; others cargo-culted the ceremonies without understanding the principles. Either way, the days of "just write code and ship it" were fading.

Code review became expected, at least at companies that considered themselves serious about engineering. Automated testing went from "nice to have" to "you should probably have this." Continuous integration systems would run your tests on every commit. The professionalization of software development was accelerating.

But the roles we take for granted today were still forming. When I started my career in 2012, I didn't have an engineering manager. I didn't have a product manager. There was no one whose job was to write tickets or prioritize the backlog or handle one-on-ones. You just had developers, maybe a designer, and someone technical enough to make decisions. A "senior developer" might have three years of experience. The org charts were flat because the companies were small and the industry was young.

By 2013, the landscape had transformed. We had powerful frameworks, easy deployment, social coding, mobile-responsive sites, cheap infrastructure, and JavaScript everywhere. The web had survived the mobile threat and emerged stronger. The pieces were in place for the next phase — one where JavaScript would take over everything and complexity would reach new heights.

The JavaScript Renaissance

"Everything is a SPA now"

Something shifted around 2013. The web had proven it could handle real applications — Gmail, Google Maps, and a generation of startups had shown that. But we were hitting the limits of how we'd been building things. jQuery and server-rendered pages got you far, but as applications grew more ambitious, the cracks started showing.

The problem was state. When your server renders HTML and jQuery sprinkles interactivity on top, keeping everything in sync becomes a nightmare. Imagine a page with a comment section — the server renders the initial comments, but when a user posts a new one, you need to somehow create that same HTML structure in JavaScript and insert it in the right place. Now imagine that comment count appears in three different places on the page. And there's a notification badge. And the comment might need a reply button that does something else. You end up with spaghetti code that's constantly fighting to keep the UI consistent with the underlying data.

The answer, everyone decided, was to move everything to the client. Single-page applications — SPAs — would handle all the rendering in the browser. The server would just be an API that returned JSON. JavaScript would manage the entire user interface.

The first wave of frameworks had already arrived. Backbone.js gave you models and views with some structure. Angular, backed by Google, went further with two-way data binding and dependency injection — concepts borrowed from the enterprise Java world. Ember.js, which I used on my first major frontend project, was the most ambitious: it tried to be the Rails of JavaScript, with strong conventions and a complete solution for routing, data, and templating.

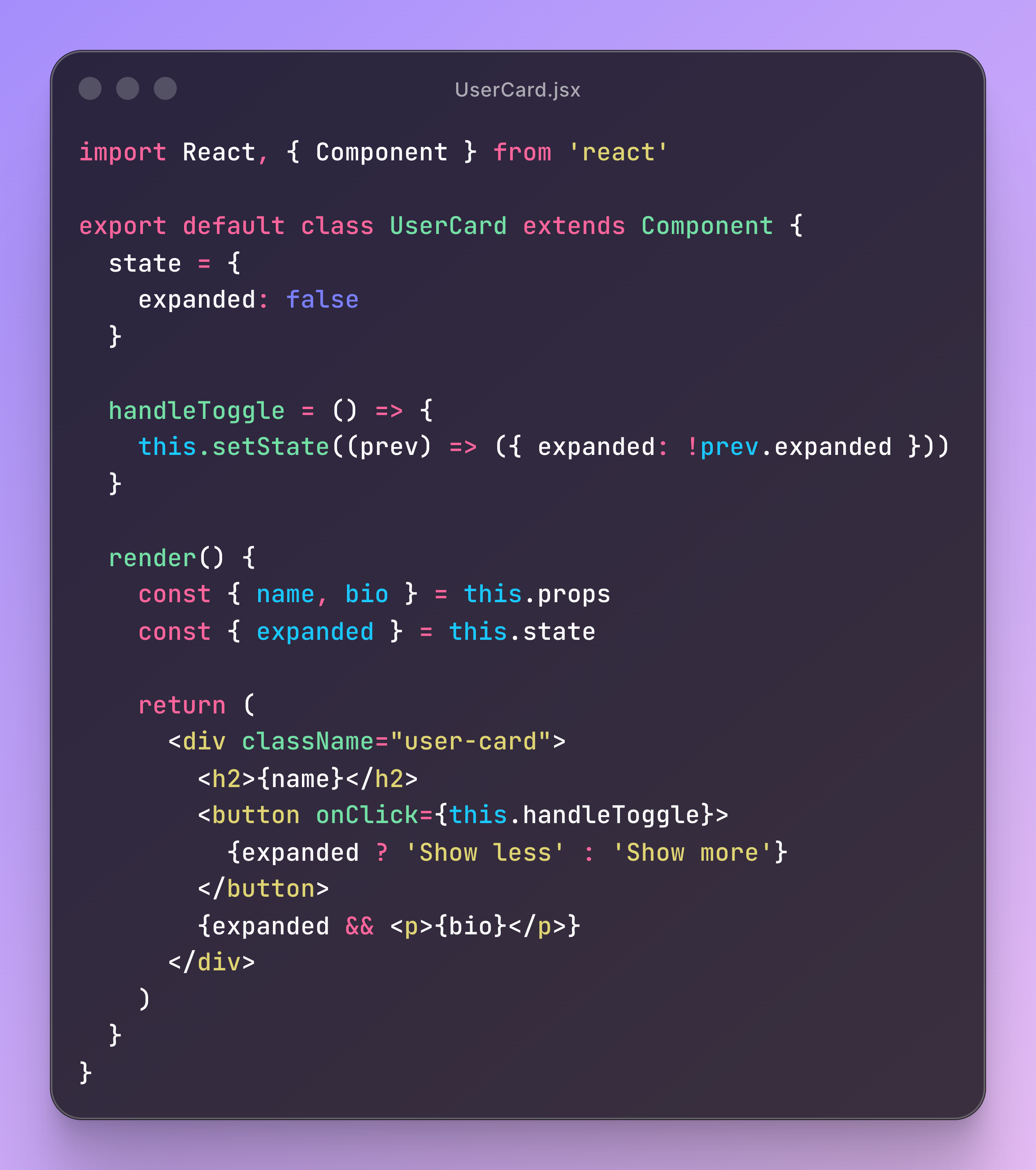

![]()

These frameworks were a step forward, but they all struggled with the same fundamental problem: keeping the DOM in sync with your data was complicated. Two-way data binding sounded great in theory — change the data and the UI updates, change the UI and the data updates — but in practice it led to cascading updates that were hard to reason about. When something went wrong, good luck figuring out what triggered what.

Then React arrived.

Facebook open-sourced React in 2013, and the initial reaction was... mixed. The syntax looked weird. JSX — writing HTML inside your JavaScript — seemed like a step backward. Hadn't we spent years separating concerns? Why would we mix markup and logic together?

But React had a different mental model, and once it clicked, everything else felt clunky. Instead of mutating the DOM directly, you described what the UI should look like for a given state. When the state changed, React figured out what needed to update. It was declarative rather than imperative — you said "the button should be disabled when loading is true" rather than writing code to disable and enable the button at the right moments.

The virtual DOM made this efficient. React would build an in-memory representation of your UI, compare it to the previous version, and calculate the minimum set of actual DOM changes needed. This sounds like an implementation detail, but it freed you from thinking about DOM manipulation entirely. You just managed state and let React handle the rest.

Components were the other big idea. You'd build small, reusable pieces — a Button, a UserAvatar, a CommentList — and compose them into larger interfaces. Each component managed its own state and could be reasoned about in isolation. This wasn't entirely new, but React made it practical in a way previous frameworks hadn't.

React took a couple of years to reach critical mass. By 2015 it was clearly winning. Vue.js emerged as a gentler alternative — similar ideas, but with a syntax that felt more familiar to people coming from Angular or traditional web development. The "framework wars" had a new set of combatants.

But here's the thing about the SPA revolution: building everything in JavaScript meant you needed a lot more JavaScript. And the JavaScript you wanted to write wasn't the JavaScript browsers understood.

ES6 — later renamed ES2015 — was a massive upgrade to the language. Arrow

functions, classes, template literals, destructuring, let and const, promises,

modules. It fixed so many of the rough edges that had made JavaScript painful.

No more var self = this hacks. No more callback pyramids of doom. The language

finally felt modern.

The problem was that browsers didn't support ES6 yet. Internet Explorer was still lurking. Even modern browsers were slow to implement all the new features. You couldn't just write ES6 and ship it.

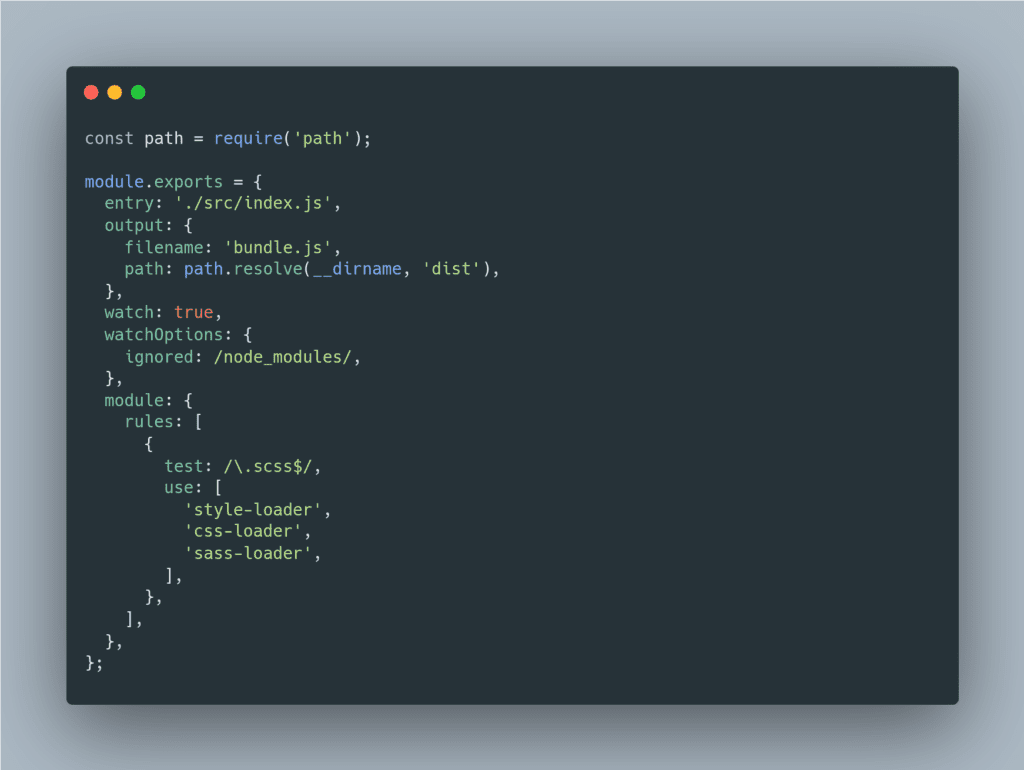

Enter Babel. Babel was a transpiler that converted your shiny new ES6 code into the old ES5 that browsers actually understood. You could write modern JavaScript today and trust the build process to make it work everywhere. This was transformative, but it also meant that writing JavaScript now required a compilation step. The days of editing a file and refreshing the browser were over.

This is how Node.js finally conquered every developer's machine — not through server-side applications, but through build tools. You might never write a Node backend, but you absolutely had Node installed because that's what ran your build process.

The tooling evolved rapidly. Grunt came first — a task runner where you'd configure a series of steps: transpile the JavaScript, compile the Sass, minify everything, copy files around. Configuration files grew long and unwieldy. Gulp came next, promising simpler configuration through code instead of JSON. You'd pipe files through a series of transformations. It was better, but still complex.

Then Webpack changed everything. Webpack wasn't just a task runner — it was a module bundler that understood your dependency graph. It would start at your entry point, follow all the imports, and bundle everything into optimized files for production. It handled JavaScript, CSS, images, fonts — anything could be a module. Code splitting let you load only what you needed. Hot module replacement let you see changes instantly without refreshing the page.

Webpack was powerful, but the configuration was notoriously difficult. Webpack config files became a meme. You'd find yourself copying snippets from Stack Overflow without fully understanding what they did, adjusting settings until things worked, terrified to touch it again. The joke was that every team had one person who understood their Webpack config, and when that person left, the config became a haunted artifact that no one dared modify.

The npm ecosystem exploded alongside all of this. Where you once downloaded

libraries manually, now you'd npm install them and import what you needed. The

convenience was incredible — need a date library? npm install moment. Need

utilities? npm install lodash. Need to pad a string on the left side?

npm install left-pad.

That last one led to one of the most absurd moments in JavaScript history. In March 2016, a developer named Azer Koçulu got into a dispute with npm over a package name. In protest, he unpublished all of his packages, including a tiny eleven-line module called left-pad that did exactly what the name suggests: pad a string with characters on the left side.

It turned out thousands of packages depended on left-pad, either directly or through some chain of dependencies. When it vanished, builds broke everywhere. Major projects — including React and Babel themselves — couldn't install their dependencies. The JavaScript ecosystem ground to a halt for a few hours until npm took the unprecedented step of restoring the package against the author's wishes.

Eleven lines of code. The whole thing felt absurd and a little scary. We'd built an incredibly powerful ecosystem on top of a foundation of tiny packages maintained by random people who could pull them at any time. The left-pad incident didn't change how we worked — the convenience of npm was too great — but it did make us realize how fragile it all was.

By 2016, the complexity had reached a peak, and people were exhausted. A satirical article titled "How it feels to learn JavaScript in 2016" went viral. It captured the bewilderment of trying to build a simple web page and being told you needed React, Webpack, Babel, Redux, a transpiler for the transpiler, and seventeen other tools before you could write a line of code. JavaScript fatigue was real. The ecosystem was moving so fast that the thing you learned six months ago was already outdated. Best practices changed constantly. It felt impossible to keep up.

And yet, we kept building. The tools were complex, but they were also capable. You could create rich, interactive applications that would have been impossible a few years earlier. The complexity was the cost of ambition.

Docker arrived in 2013 and quietly started solving a completely different problem. Remember "works on my machine"? Docker promised to end it forever. You'd define your application's environment in a Dockerfile — the operating system, the dependencies, the configuration — and Docker would package it into a container that ran identically everywhere. Your laptop, your colleague's laptop, the staging server, production — all the same.

Containers weren't a new concept. Linux had the underlying technology for years.

But Docker made it accessible. You didn't need to understand cgroups and

namespaces; you just wrote a Dockerfile and ran docker build. The abstraction

was good enough that regular developers could use it without becoming

infrastructure experts.

Adoption was bumpy at first. Docker on Mac was slow and flaky for years. Networking between containers was confusing. The ecosystem was fragmented — Docker Compose for local development, Docker Swarm for orchestration, and then Kubernetes emerged from Google and started winning the orchestration war. By 2017 it was clear that containers were the future, even if the details were still being sorted out.

The microservices trend rode alongside Docker. Instead of one big application, you'd build many small services that communicated over the network. Each service could be deployed independently, scaled independently, written in whatever language made sense. In theory, this gave you flexibility and resilience. In practice, you'd often traded the complexity of a monolith for the complexity of a distributed system. Now you needed service discovery, load balancing, circuit breakers, distributed tracing. Many teams learned the hard way that microservices weren't free.

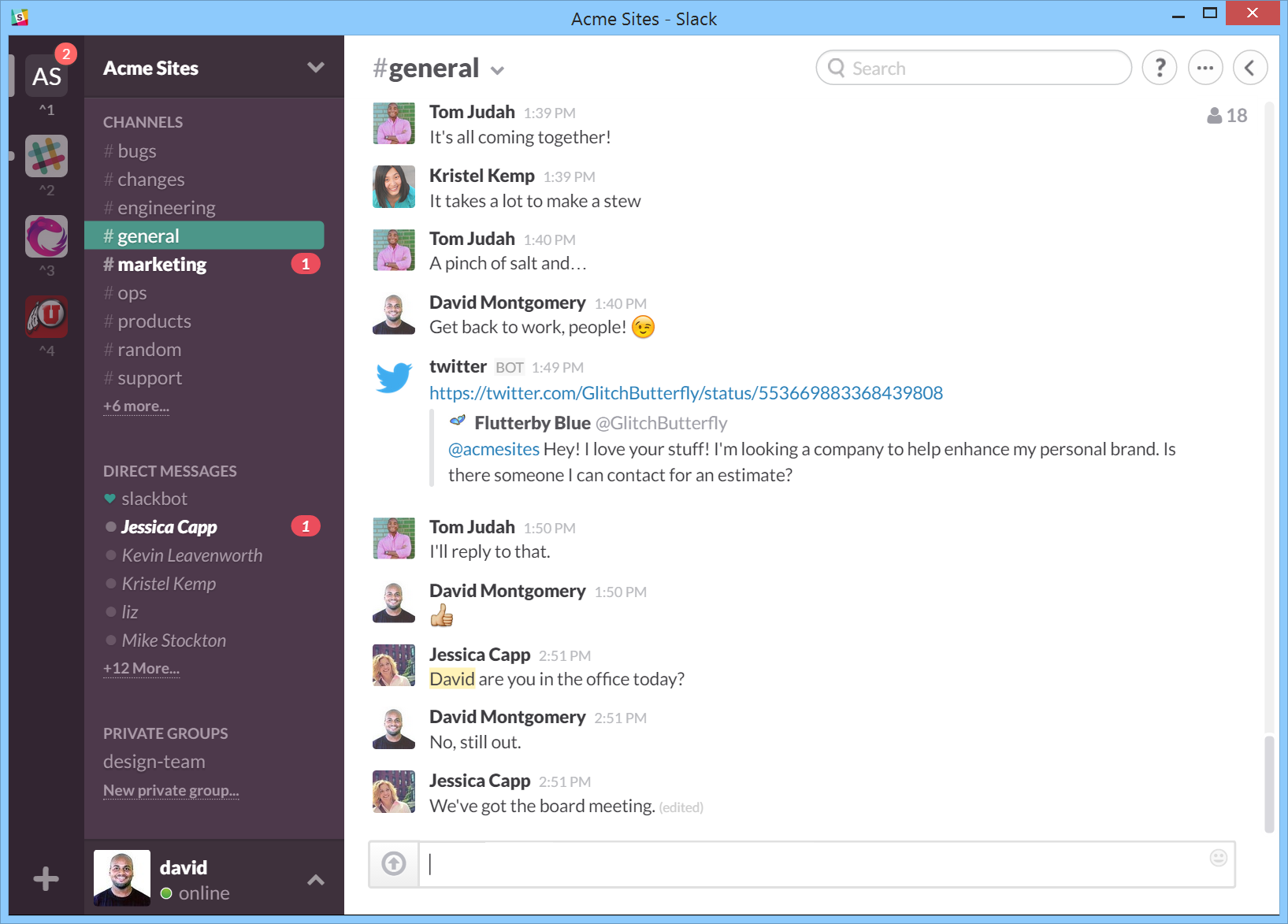

The big web applications were getting really good during this period. Slack launched in 2013 and somehow made work chat feel fun. It was fast, searchable, and had integrations with everything. The threaded conversations, the emoji reactions, the GIFs — it felt like software made by people who actually used it. Slack replaced email for a lot of workplace communication, for better or worse.

Figma launched in 2016 and proved that even serious creative tools could run in a browser. Design software had always meant big desktop applications — Photoshop, Sketch, Illustrator. Figma gave you collaborative design in a browser tab. Multiple people could work on the same file simultaneously. No more emailing PSDs around. No more "which version is the latest?" Figma was fast enough and capable enough that designers actually switched.

These applications — Slack, Figma, Notion (which launched in 2016 too), and others — demonstrated what modern web development could achieve. They were ambitious in a way that validated all the complexity. Sure, you needed Webpack and React and a build process, but look what you could build with them.

The role of product manager had become standard by now. When I started in 2012, a PM was something big companies had. By 2016, even small startups expected to have product people writing tickets and prioritizing backlogs. Engineering managers emerged as a distinct role from tech leads — one focused on people and process, the other on technical decisions. The flat, informal teams of the earlier era were giving way to more structured organizations.

Scrum was everywhere, for better or worse. Standups, sprint planning, retrospectives, story points, velocity charts. Some teams found it genuinely helpful; others went through the motions without understanding why. The ceremonies could feel like overhead, especially when poorly implemented, but the underlying ideas — short iterations, regular reflection, breaking work into small pieces — had real value.

By 2017, the dust was starting to settle. React had won the framework war, more or less. Webpack was painful but standard. ES6 was just how you wrote JavaScript. Docker was becoming normal. The ecosystem was still complex, but it was stabilizing. Developers who'd stuck it out had powerful tools at their disposal.

The next era would bring consolidation. TypeScript would finally make JavaScript feel like a real programming language. Meta-frameworks like Next.js would tame some of the complexity. And deployment would get dramatically simpler. But first, we had to survive the JavaScript renaissance — and despite the fatigue, most of us came out the other side more capable than we'd ever been.

The TypeScript Era

"Types are good, actually"

After the chaos of the JavaScript renaissance, something unexpected happened: things calmed down. Not completely — this is still web development — but the frantic churn of new frameworks and tools slowed to something more manageable. The ecosystem started to mature. And quietly, TypeScript changed how we thought about JavaScript entirely.

TypeScript had been around since 2012, created by Microsoft to bring static typing to JavaScript. For years, most developers ignored it. JavaScript was dynamic and that was fine. Types were for Java developers who liked writing boilerplate. Adding a compilation step just to get type checking seemed like overkill for a scripting language.

But as JavaScript applications grew larger, the problems with dynamic typing

became harder to ignore. You'd refactor a function, change its parameters, and

spend the next hour tracking down all the places that called it with the old

signature. You'd read code written six months ago and have no idea what shape of

object a function expected. You'd deploy to production and discover a typo —

user.nmae instead of user.name — that a type checker would have caught

instantly.

TypeScript adoption started accelerating around 2017-2018. Once you tried it on a real project, it was hard to go back. The autocomplete alone was worth it — your editor actually understood your code and could suggest what came next. Refactoring became safe. Interfaces documented your data structures in a way that couldn't drift out of sync with the code.

The turning point was when the big frameworks embraced it. Angular had been TypeScript-first from the start, but Angular was also verbose and enterprise-y. When React's type definitions matured and Vue 3 was rewritten in TypeScript, it became clear this wasn't just a niche preference. By 2020, starting a new project in plain JavaScript felt almost irresponsible.

TypeScript also changed who could contribute to a codebase. In a dynamically typed project, you needed to hold a lot of context in your head — or dig through code to understand what types things were. TypeScript made codebases more approachable. A new team member could read the interfaces and understand the domain model without archaeology. The types were documentation that the compiler kept honest.

The tooling matured around the same time. VS Code, which Microsoft had released in 2015, became the dominant editor. It was fast, free, and had TypeScript support baked in from the start. The combination of VS Code and TypeScript created a development experience that felt genuinely good — intelligent autocomplete, inline errors, refactoring tools that actually worked. Sublime Text and Atom faded. Even vim devotees started grudgingly admitting that VS Code was pretty nice.

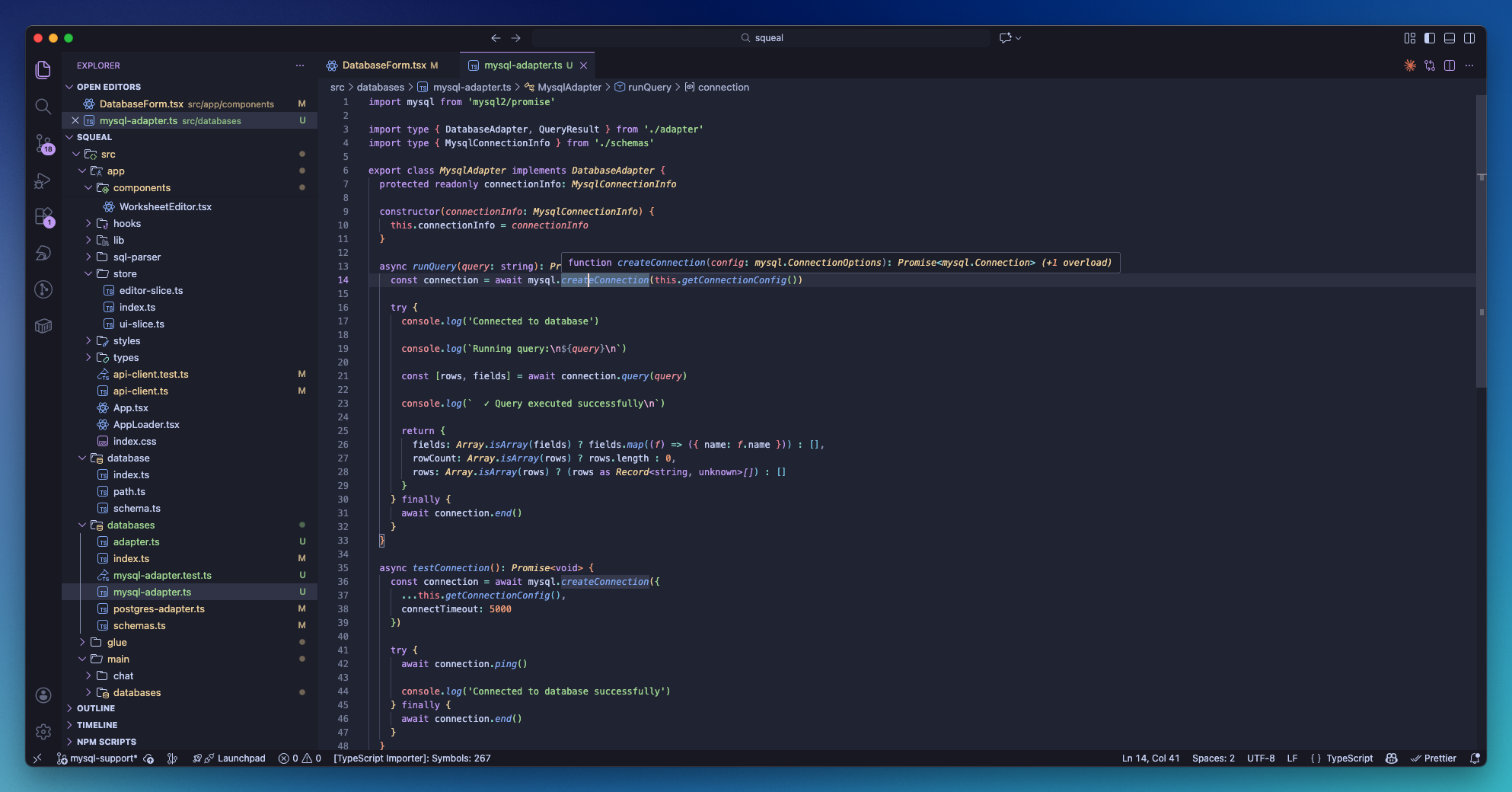

While TypeScript was bringing sanity to the language, another layer of abstraction was emerging on top of React. The problem was that React itself was just a UI library. It told you how to build components, but it didn't have opinions about routing, data fetching, server rendering, or code splitting. Every React project had to make these decisions from scratch, and every team made them differently.

Next.js, created by Vercel, stepped in to fill this gap. It was a meta-framework — a framework built on top of React that made the common decisions for you. File-based routing: drop a file in the pages folder and it becomes a route. Server-side rendering: works out of the box. API routes: add a file to the api folder and you have a backend endpoint. Code splitting: automatic.

Next.js wasn't the only option. Nuxt did the same for Vue. Remix, created by the React Router team, emerged later with a different philosophy that leaned harder on web standards and progressive enhancement. SvelteKit gave the Svelte community their answer. Gatsby was popular for static sites. But Next.js became the default choice for React projects, to the point where "React app" and "Next.js app" became almost synonymous.

This consolidation was a relief after the fragmentation of the previous era. You could start a new project without spending a week on tooling decisions. The meta-frameworks handled webpack configuration, Babel setup, and all the other infrastructure that used to require careful assembly.

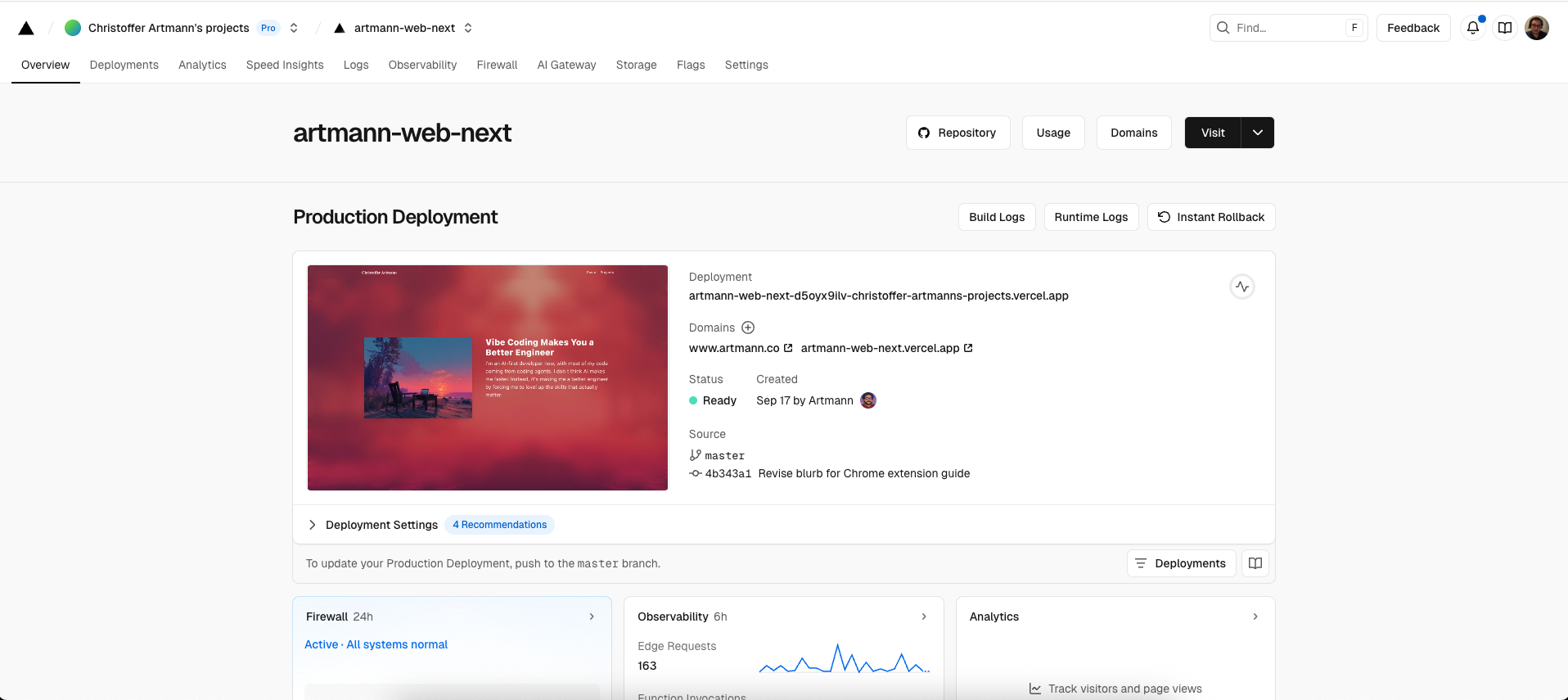

Deployment was getting dramatically simpler too. Vercel and Netlify had been around for a few years, but they really hit their stride in this era. The pitch was simple: connect your GitHub repo, and every push triggers a deployment. Pull requests get preview deployments with unique URLs. Production deploys happen automatically when you merge to main. No servers to manage, no CI/CD pipelines to configure, no Docker images to build.

This wasn't just convenience — it changed workflows. Product managers and designers could preview changes before they merged. QA could test feature branches in realistic environments. The feedback loop tightened dramatically. And the free tiers were generous enough that you could run real projects without paying anything.

Railway and Render emerged as alternatives that handled more traditional backend applications. Heroku, the pioneer of push-to-deploy, started feeling dated — its free tier got worse, its interface felt neglected, and the DX that had once been revolutionary now seemed merely adequate. The new platforms were eating its lunch.

Serverless was the other deployment story of this era. AWS Lambda had launched back in 2014, but it took years for the ecosystem to mature. The idea was appealing: instead of running a server 24/7 waiting for requests, you'd write functions that spun up on demand, ran for a few seconds, and disappeared. You paid only for what you used. Scaling was automatic — if a million requests came in, a million functions would spin up to handle them.

In practice, serverless had rough edges. Cold starts meant the first request after idle time was slow. State was hard — functions were ephemeral, so you couldn't keep anything in memory between requests. Debugging was painful. The local development story was poor. Vendor lock-in was real. But for certain use cases — APIs with spiky traffic, scheduled jobs, webhook handlers — serverless made a lot of sense. Cloudflare Workers pushed the model further, running functions at the edge, close to users, with even faster cold starts.

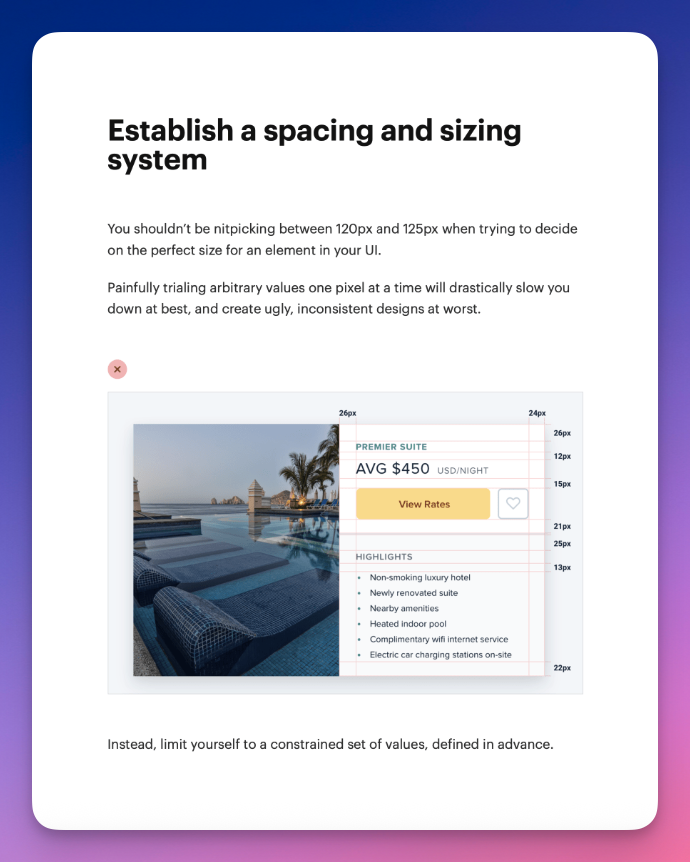

CSS was having its own quiet revolution. For years, the answer to CSS complexity was preprocessors — Sass or Less — that added variables, nesting, and mixins. Then came CSS-in-JS, where you'd write styles in your JavaScript files, colocated with components. Styled-components and Emotion were popular. It solved some real problems around scoping and dynamic styles, but it also felt heavyweight. You were shipping a runtime just to apply CSS.

Tailwind CSS arrived in 2017, but it reached

mainstream adoption around 2020. The premise was counterintuitive: instead of

writing semantic class names and then defining styles separately, you'd use

utility classes directly in your HTML. A button might have the classes

bg-blue-500 text-white px-4 py-2 rounded hover:bg-blue-600. Your markup looked

cluttered with all these classes, and everyone's first reaction was visceral

discomfort.

But once you tried it, something clicked. You stopped context-switching between HTML and CSS files. You stopped inventing class names. You stopped worrying about the cascade and specificity. The utility classes were constrained enough that designs stayed consistent. And because you never wrote custom CSS, your stylesheets stayed tiny. The approach wasn't for everyone — designers who loved crafting CSS hated it, and it felt wrong if you'd internalized the separation of concerns gospel — but for developers who just wanted to style things and move on, Tailwind was a revelation.

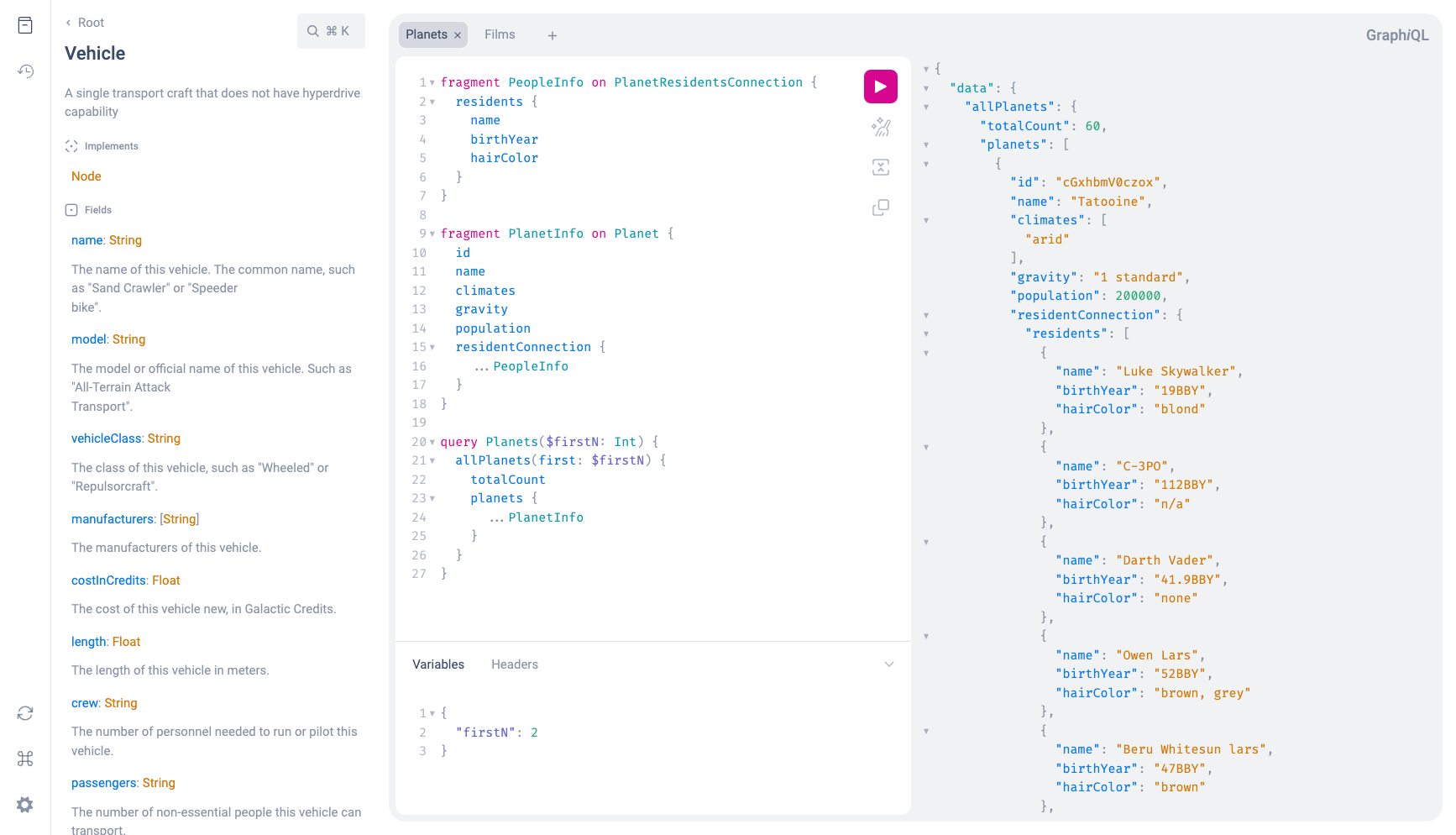

GraphQL had its peak during this era. Facebook had released it in 2015 as an alternative to REST APIs. Instead of hitting multiple endpoints and getting back whatever the server decided to send, you'd write a query specifying exactly what data you wanted. The server would return exactly that, no more, no less. No overfetching, no underfetching. Frontend and backend could evolve independently, connected by a typed schema.

The developer experience was genuinely good. Tools like Apollo Client managed caching and state. GraphiQL let you explore APIs interactively. The typed schema meant you could generate TypeScript types automatically. For complex applications with lots of nested data, GraphQL was elegant.

But GraphQL also brought complexity. You needed a GraphQL server layer. Caching was harder than REST. N+1 query problems were easy to create. For simple CRUD applications, it was overkill. By the end of this era, the hype had cooled. GraphQL remained popular for complex applications and public APIs, but many teams quietly stuck with REST or moved to simpler alternatives like tRPC, which gave you type safety without the ceremony.

Kubernetes won the container orchestration war, for better or worse. Docker had solved packaging applications into containers, but running containers in production at scale needed something more. For a while, Docker Swarm, Kubernetes, Mesos, and others competed. By 2018, Kubernetes was the clear winner. Google had designed it based on their internal systems, donated it to the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, and it became the standard way to run containers in production.

Kubernetes was powerful and flexible, but it was also complex. The learning curve was steep. YAML configuration files sprawled across your repository. You needed to understand pods, services, deployments, ingresses, config maps, secrets, and a dozen other abstractions just to deploy a simple app. Managed Kubernetes services like GKE, EKS, and AKS helped, but there was still a lot to learn.

For many teams, Kubernetes was overkill. If you weren't running dozens of services at scale, the operational overhead didn't justify the benefits. The new PaaS platforms — Vercel, Render, Railway — were partly a reaction to this. They'd handle the infrastructure complexity for you. You didn't need to know about Kubernetes; you just pushed code. The abstraction level kept rising.

Then COVID happened.

In March 2020, the world went remote almost overnight. Software teams that had been office-based suddenly had to figure out how to work distributed. The tools existed — Slack, Zoom, GitHub — but the workflows hadn't been tested at this scale.

For web development specifically, the impact was a boom. Everyone needed digital everything. Companies that had planned to "eventually" build web applications needed them now. E-commerce exploded. Collaboration tools exploded. Anything that could move online did. Developer tools companies raised huge funding rounds. Vercel became a unicorn. The demand for software far exceeded the supply of people who could build it.

Remote work also changed team dynamics. Asynchronous communication became more important. Documentation mattered more when you couldn't tap someone on the shoulder. Pull request descriptions got more thorough. The tools we'd been building all along — GitHub's code review, Notion for docs, Slack for chat — turned out to be exactly what distributed teams needed.

The organizational side of software development kept maturing. Engineering ladders became standard — clear paths from junior to senior to staff to principal engineer. The IC (individual contributor) track gained legitimacy as an alternative to management. You could become a staff engineer without managing people, recognized for technical leadership rather than people leadership.

Engineering managers and product managers were now expected at any company above a certain size. The two roles had differentiated clearly: PMs owned what to build and why, EMs owned how the team worked and people development, tech leads owned technical decisions. The flat, informal structures of the early startup era persisted at very early-stage companies, but they were the exception now.

Developer experience — DX — emerged as a discipline. Companies realized that making developers productive was worth investing in. Internal platform teams built tools and abstractions so product engineers didn't have to think about infrastructure. Good documentation, smooth onboarding, fast CI pipelines — these things started getting attention and resources.

By 2022, the web development landscape looked remarkably different from five years earlier. TypeScript was the default. Next.js dominated React projects. Deployment was trivially easy. Tailwind had won over skeptics. The tooling was mature and capable. Yes, there was still complexity — there would always be complexity — but it felt manageable. The JavaScript fatigue of 2016 had given way to something like contentment.

And then everything changed again. A company called OpenAI released something called ChatGPT.

The AI Moment

"Wait, I can just ask it to write the code?"

Every era in this retrospective had its defining moment — the thing that made you realize the rules had changed. Gmail showing us what AJAX could do. React changing how we thought about UI. TypeScript making JavaScript feel grown-up. But nothing prepared us for November 30, 2022.

That's when OpenAI released ChatGPT.

Within a week, everyone was talking about it. Within a month, it had a hundred million users. The interface was almost comically simple — a text box where you typed questions and got answers — but what came out of it was unlike anything we'd seen. You could ask it to explain quantum physics, write a poem in the style of Shakespeare, or debug your Python code. And it would just... do it. Not perfectly, not always correctly, but well enough that it felt like magic.

Developers started experimenting immediately. Could it write a React component? Yes, pretty well actually. Could it explain why your code wasn't working? Often better than Stack Overflow. Could it convert code from one language to another? Surprisingly competently. The things that used to require hours of documentation reading or forum searching now took seconds.

GitHub Copilot had actually arrived earlier, in June 2022, but ChatGPT was what made AI feel real to most people. Copilot worked differently — it lived inside your editor, watching what you typed and suggesting completions. Start writing a function name and it would guess the implementation. Write a comment describing what you wanted and it would generate the code below. It was autocomplete on steroids.

The experience was strange at first. You'd start typing and this ghost text would appear, offering to finish your thought. Sometimes it was exactly what you wanted. Sometimes it was subtly wrong. Sometimes it hallucinated APIs that didn't exist. You had to develop a new skill: evaluating AI suggestions quickly, accepting the good ones, tweaking the close ones, rejecting the nonsense.

But when it worked, it worked remarkably well. Boilerplate code that used to take ten minutes took ten seconds. Unfamiliar libraries became approachable because Copilot knew their APIs even if you didn't. The tedious parts of programming — writing tests, handling edge cases, converting data between formats — got faster. You could stay in flow instead of constantly switching to documentation.

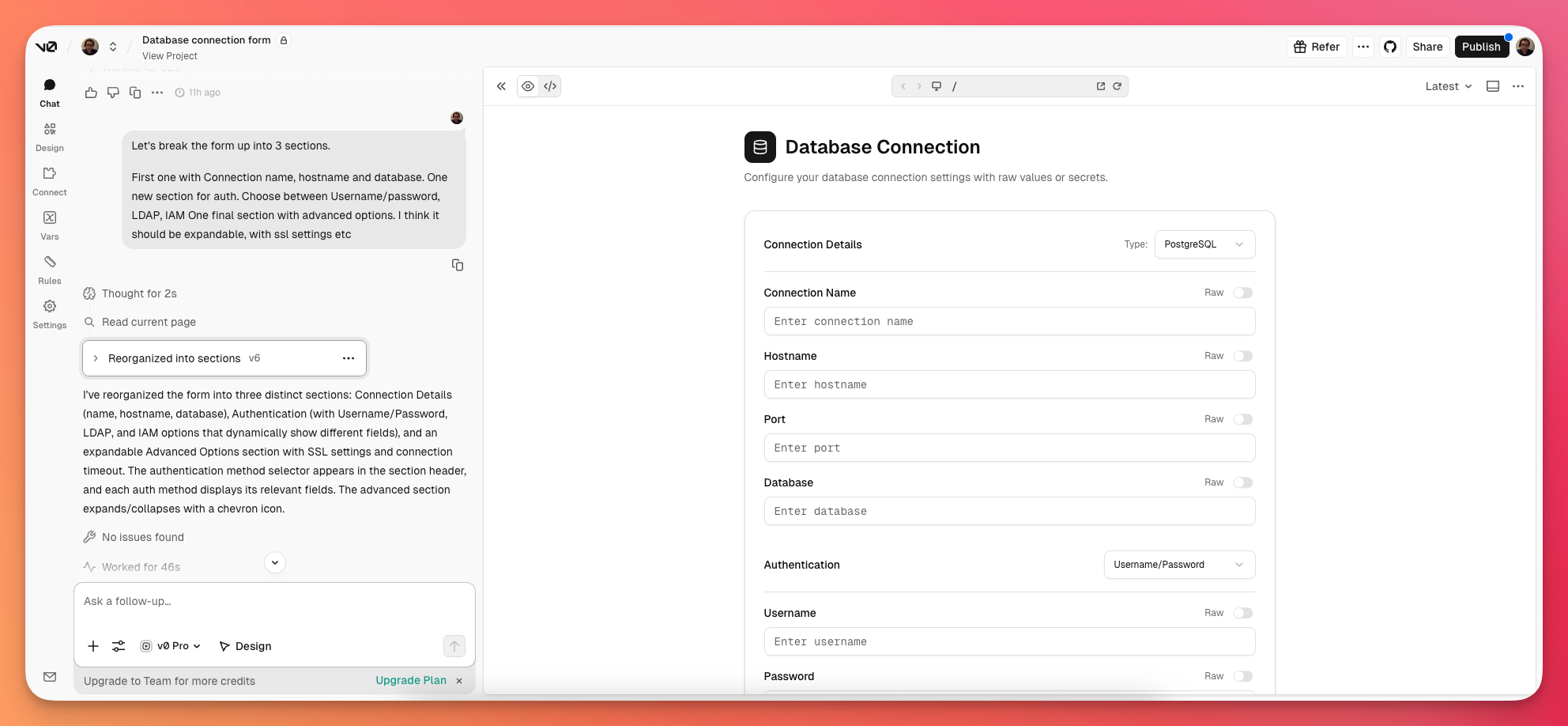

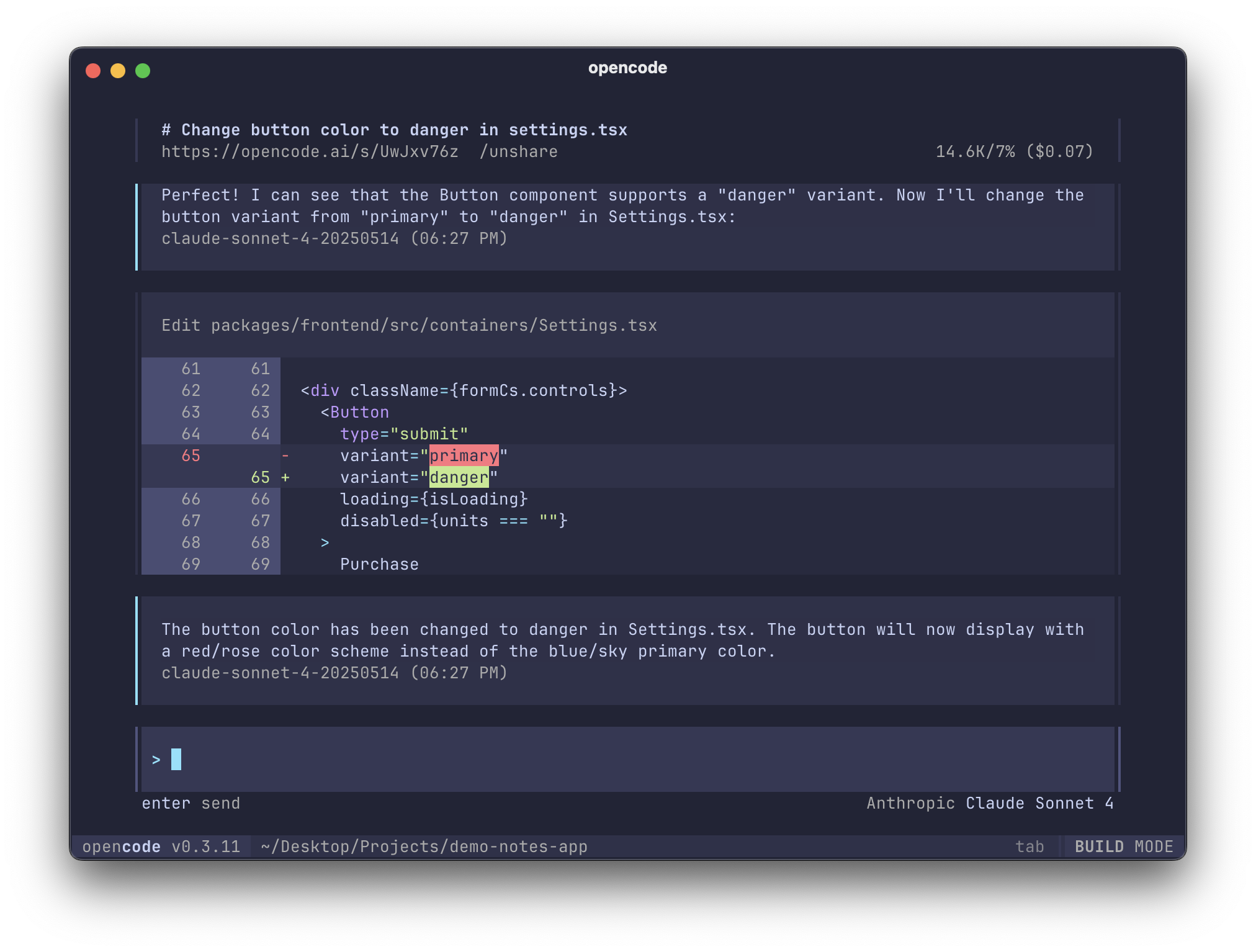

Cursor took this further. It launched in 2023 as a fork of VS Code rebuilt around AI. The difference was integration — instead of AI being a feature bolted onto your editor, the entire experience was designed around it. You could select code and ask Cursor to refactor it. You could describe a feature in plain English and watch it write across multiple files. You could have a conversation with your codebase.

The implications were disorienting. Skills that had taken years to develop — knowing APIs, remembering syntax, understanding patterns — suddenly mattered less. A junior developer with good prompting skills could produce code that looked like it came from someone with a decade of experience. What did seniority even mean when the AI knew more syntax than anyone?

The answer, it turned out, was that seniority still mattered — just differently. The AI could write code, but it couldn't tell you what code to write. It didn't understand your business requirements, your users, your technical constraints. It didn't know which shortcuts would come back to haunt you and which were fine. It would confidently generate solutions to the wrong problem if you weren't careful. The job shifted from writing code to directing code — knowing what to ask for, evaluating what came back, understanding the system well enough to spot when the AI was leading you astray.

The discourse was polarized, predictably. Some people declared that programming was dead, that we'd all be replaced by AI within two years. Others dismissed the whole thing as hype, insisting that AI-generated code was buggy garbage that real engineers would never use. The truth was somewhere in between and more interesting than either extreme. AI didn't replace developers, but developers who used AI became noticeably more productive. You could attempt projects that would have been too tedious before. You could learn new domains faster. You could build more.

I found myself building things I wouldn't have attempted a few years ago. Side projects that would have taken months became weekend experiments. Areas where I had no expertise — machine learning, game development, unfamiliar frameworks — became accessible because I could have a conversation with something that knew more than I did. The barrier to trying new things dropped dramatically.

This was the democratization story continuing, but accelerated. The web had always been about lowering barriers — from needing a server to needing just FTP, from needing C to needing just PHP, from needing operations knowledge to needing just git push. AI was the next step: from needing to know how to code to needing to know what you wanted to build.

Non-developers started building things. Product managers prototyping features. Designers implementing their own designs. Domain experts creating tools for their specific needs. The line between "technical" and "non-technical" blurred. You still needed developers for anything complex or production-grade, but the definition of what required a developer was shrinking.

The indie hacker movement flourished. Solo developers shipping products that competed with funded startups. People building and launching MVPs in days instead of months. Twitter was full of people documenting their journeys building SaaS products alone. Some of it was survivorship bias and hustle culture, but some of it was genuinely new. The tools had become powerful enough that one person really could build something meaningful.

While AI was the main story, the ecosystem kept evolving in other ways. React Server Components, after years of development, started seeing real adoption. The idea was to render components on the server by default, sending only the HTML to the browser, and explicitly marking components as client-side when they needed interactivity. It was a philosophical shift — instead of shipping JavaScript and rendering on the client, you'd do as much as possible on the server.

htmx emerged as a more radical alternative. Its premise was that you didn't need a JavaScript framework at all for most applications. Instead, you'd add special attributes to your HTML that let elements make HTTP requests and update parts of the page. Your server returned HTML fragments, not JSON. No build step, no virtual DOM, no bundle size concerns. For certain types of applications — content sites, CRUD apps, anything that didn't need rich client-side interactivity — htmx was delightfully simple.

This "use the platform" sentiment extended beyond htmx. Web standards had gotten genuinely good while we weren't paying attention. CSS had flexbox, grid, container queries, cascade layers, and native nesting. You could do most of what Sass offered in plain CSS now. JavaScript had top-level await, private class fields, and all the features we used to need Babel for. The gap between what we wanted and what browsers provided had narrowed enough that sometimes you didn't need the abstraction layer.

Bun launched in 2022 as an alternative to Node.js, promising to be dramatically faster. It was a new JavaScript runtime written in Zig, with a built-in bundler, test runner, and package manager. The benchmarks were impressive, and the developer experience was good. Whether it would actually replace Node remained to be seen, but it represented the kind of ambitious rethinking that keeps ecosystems healthy.

The job market went through turbulence. The hiring frenzy of 2021-2022, when every tech company was growing aggressively, reversed sharply in late 2022 and 2023. Layoffs swept through the industry. Companies that had hired thousands suddenly let thousands go. Interest rates rose, funding dried up, and the growth-at-all-costs mentality shifted to profitability.

For developers, this was jarring. The market that had felt infinitely abundant — where recruiters flooded your inbox and companies competed to hire you — tightened considerably. Junior roles became harder to find. The question of whether AI would reduce demand for developers mixed uncomfortably with the reality that demand was already reduced for macroeconomic reasons.

By 2024 and 2025, things had stabilized somewhat. The layoffs slowed. Companies were still hiring, just more selectively. AI hadn't replaced developers, but it had changed expectations. You were expected to be productive with AI tools. Not using them started to look like stubbornly refusing to use an IDE.

The AI capabilities kept improving. Claude, GPT-4, and other models got better at understanding context, writing longer coherent passages of code, and reasoning through problems. Coding agents — AI that could not just suggest code but actually execute it, run tests, and iterate — moved from research demos to usable tools. The pace of improvement showed no signs of slowing.

Looking at web development in late 2025, I feel remarkably optimistic. The tools have never been this good. You can go from idea to deployed application faster than ever. The platforms are mature, the frameworks are capable, the deployment is trivial. AI handles the tedious parts and helps you learn the parts you don't know yet.

Switching computers used to be a multi-day ordeal — reinstalling software, copying files, reconfiguring everything. Now I install a handful of apps and log in to services. Everything lives in the cloud. My code is on GitHub, my documents are in Notion, my designs are in Figma. The computer is almost just a terminal into the real environment that exists online.

Thirty years ago, my dad set up a Unix server so I could upload HTML files about

whatever interested me that week. The tools were primitive, the sites were ugly,

and everything was held together with <br> tags and good intentions. But the

core promise was there: anyone could build and share on the web.

That promise has only grown stronger. The barriers keep falling. What once required a team now takes a person. What once took weeks now takes hours. The web remains the most accessible platform for creation that humans have ever built.

I don't know exactly where this goes next. AI is moving fast enough that predictions feel foolish. But the trajectory of my entire career has been toward more people being able to build more things more easily. I don't see any reason that stops.

It's a fantastic time to be building for the web.